Chris Broughton, 1949 – 2015

“Working on the Journals has allowed me to experiment with illustrative illusion to communicate in visually interesting ways, gathering information from walking, sketching, and taking photographs, and working in my studio on drawings that help to explain and enhance the reader’s understanding and enjoyment of the text. I would say that the most interesting drawings to do are the overviews (probably inspired by reading too many Rupert stories), which, while not topographically correct try to give the reader an idea of a complete landscape and evoke a ‘sense of place’.”

For New Arcadian and other illustrations by Chris Broughton, visit chrisbroughtonartist.co.uk

![]()

Patrick Eyres and Chris Broughton (right) at Melbourne Hall, Derbyshire, 2010. Photo: Howard Eaglestone.

Remembering Chris

Patrick Eyres, Lawnswood Crematorium, Leeds, 24 August 2015

Family and drawing, drawing and family. These were at the heart of Chris’s life. We all know how proud he was of his family, and we all know of his devotion to drawing.

The week before his death I had a remarkable conversation with Chris – a conversation I hadn’t anticipated, perhaps because us blokes don’t expect to speak about feelings. First, Chris told me he was no longer capable of drawing. Then he said that, of all his drawings, those created for the New Arcadian Journal had given him the greatest enjoyment. Moreover, these drawings had brought him a close circle of friendship with artists and writers he’d met through the Journal. He went on to say he was so proud that these drawings had contributed to the conservation of historical landscapes in Britain.

For my part, I was keen to remind him of the audiences that admired his drawings – such as: the lovers of landscape gardens, the heritage professionals engaged in conserving historic landscapes, the academics who teach landscape architecture, landscape design and landscape history, and the students of these disciplines, as well as the collectors of illustrated books. Moreover, through the Journal, Chris’s drawings had found a home in library collections across Britain, Europe and the United States, and in Canada, Australia, Japan and Taiwan. I was also able to tell him that a younger generation of artists had become fans of the Journal.

He then asked me to speak at his funeral – in fact, to speak about the drawings for the New Arcadian Journal. Not surprisingly, my words have turned out to be a summary of all our chats since the diagnosis that his tumour was inoperable. We’d rambled down the leafy lanes of memory, chuckling about the high points of all the years we’d worked together – such as the sun-soaked walks through idyllic landscapes, and we surprised ourselves by remembering that all our annual jaunts were fortuitously bathed in sunshine. As a reminder, I’d emailed a photo of him and Andrew Naylor in a meadow of wild flowers beside the Palladian Bridge in the landscape garden at Wotton, and we’d wallowed in the nostalgia of being chauffeured round the gardens of Buckinghamshire in Andrew’s vintage Citroen DS. We’d also chatted about the daft moments – such as the time that my new neighbour had asked if the other tubby bald bloke was my brother.

It was thirty years ago today, as Sergeant Pepper might have said, that we first talked about drawings for the New Arcadian Journal. Since then, 613 drawings have been published in twenty-seven editions of the Journal. I can be so precise because I’ve counted them. Among these are ninety bird’s-eye views of landscapes and gardens – and each one of these is complex, imaginative and wondrous to behold. Moreover, when the drawings for New Arcadian broadsheets, posters and cards, as well as those New Arcadian drawings placed in other books, magazines and newspapers are added to the 613 published in the Journal, the full tally is nearer to 700 published drawings.

This is an extraordinary achievement and it speaks of Chis’s compulsive devotion to drawing, and of his love of gardens, landscape, history, place and book illustration – all of which was spurred on by his delight in Dan Dare, The Eagle comic, Dinky Toys, Hornby double-O train sets, as well as by the precedent of favourite artists – such as the robust graphics of Edward Bawden and the graphic lyricism of Eric Ravilious. Yet Chris was thoroughly up-to-date and enthusiastically embraced the computer as an aid to drawing – initially to help him organise the bird’s-eye views, though over the past couple of years he was drawing exclusively on his I-Pad.

Along with the drawings came the intimacy of friendship, the annual jaunts to walk the landscapes engaged by each Journal, the genteel banter and the reflective conversations – often in Headingley’s ‘Arcadia’ pub, later in the ‘Horse and Farrier’ in Otley, later still in his own home. There were so many jaunts to walk landscape gardens – in Yorkshire and across the country – and our annual expedition always combined the jaunt with a jolly-up. Chris and Howard would organise the accommodation and transport, while I arranged the visits. One remarkable summer – on the Purbeck coast of Dorset – instead of staying in a pub or hotel (that is, somewhere with a bar), we stayed in a mobile home outside Swanage – and the boys excelled themselves. Chris conjured up cordon bleu cuisine, which was complemented by Howard’s opening of a case of exquisite red wine.

Chris’s prolific drawing for the Journal was a labour of love, and he also contributed in other ways that spoke of his great generosity of spirit – for example, he always shared ideas and expertise, and always prepared for print the drawings of all the other contributing artists. Throughout the twenty years of analogue printing, he made a correctly sized bromide of each one of the hundreds of drawings – and later, once the Journal entered the digital age, he helped with the production of jpegs.

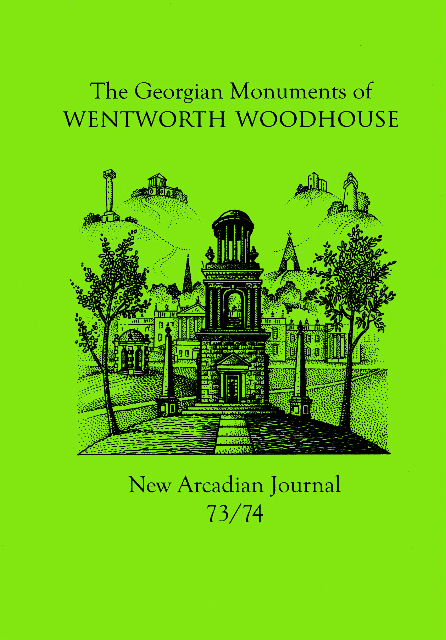

Chris’s understanding of, and pleasure in the graphic language of book illustration meant that he was the quintessential illustrator. He always sought to create drawings that would animate the texts and enhance the reader’s appreciation of the places under discussion. He relished creating designs for covers and flyleaves and also motifs, as well as the illustrations to occupy a half page, a full page and a double page spread.

His cover designs uniquely summarised the Journal’s content in a single image – by encapsulating the architectural features of a place so tantalisingly that the reader yearns to open the book. His flyleaves amplify the intimation of content and serve as mouth-watering trailers for what is yet to come. His plethora of motifs were created to decorate pages, as well as to punctuate the progress of the book.

His annual challenge, which always fascinated him, was to solve the problem of encompassing in each bird’s-eye view the way that the architecture, water and plantations shapes each landscape garden – and, year in, year out, he astonished with his imaginative compositions and visionary execution. The bird’s-eyes were always realised with such accomplishment that they became a signature feature of his art and also of the New Arcadian Journal.

His first bird’s-eye for the Journal came about through a horrific experience – horrific for me, that is, but exultant for Chris. We were visiting the three-storey Rockingham Monument while it was under restoration. The craftsmen invited us to ascend the scaffolding. I got as far as the wobbly ladder that spanned the massive void of space within the open archway of the second storey and, overwhelmed by vertigo, descended in abject terror. However Chris scampered up the ladders with the agility of a steeplejack – and he went even further up than the dome of the rotunda that caps the third storey. He went fifty feet higher – in his imagination, and his vision soared above the building, and over the park that is so rich in follies, to the gargantuan palace that is Wentworth Woodhouse, outside Rotherham – and then, as though on one of Rupert Bear’s magical adventures, he flew on to the mansion and folly-studded parkland of Wentworth Castle, six miles beyond, towards Barnsley. All this, he encompassed in his breath-taking bird’s-eye view of The Wentworths.

After this, whenever I walked with Chris, I always imagined his vision was hovering a hundred feet above us, drinking in the details of the landscape so that, once again, he would amaze with the creativity of his bird’s-eye views – and it is the bird’s-eye views that are universally admired.

Paradoxically, as his mobility decreased, his output increased – so that the two most recent Journals are embellished with 102 of his drawings – that’s a sixth of all the 613 drawings published in the Journal over the past thirty years. When his palliative care began, he told me he was determined to draw right up to the very end of his life.

So, we compiled a list of eleven landscapes that are vital to the next Journal – and thus he began the final chapter in his lifetime of drawing. Indeed it proved to be his most sustained period of drawing the complex and visionary bird’s-eye views. I must admit I regarded eleven as an over-optimistic wish-list, especially as his challenge was to imagine these places as they would have been in the year 1800.

Thank goodness for the internet and the network of researchers who supplied imagery to help Chris in this self-appointed task – a task that speaks so eloquently of the determination of his creative spirit, as well as the stoic courage with which he endured those months. Each time I visited he was chuffed to show me either a finished drawing or one in progress. He was even more chuffed to see that one was published in an online article in July. Yet, to my amazement he completed all bar one of these subjects – and wryly joked that his medication rendered these final bird’s-eyes “a tadge surreal”. It was the week before he died that he told me that the tenth was finished, but that he was unable to undertake the eleventh.

On the final visit, which proved to be the day before he died, Howard and I were keen to say as much as possible to him, even though he was unable to speak – yet Chris responded to all we said with a series of ‘thumbs-up’. I told him of my conversation that morning with an American academic who had explained that he admired the bird’s-eye views because in them Chris encapsulates gardens as landscapes of ideas. Howard spoke for us both when he told Chris that his drawings combined the precision of the London Underground map with the magic of Rupert Bear.

You can share Chris’ enjoyment of all his drawings on the website created for him by his son, David, which – as you can imagine – gave Chris great pleasure in the past couple of months. You can also see the New Arcadian drawings in action as journal covers, as broadsheets, as posters and as cards on the website of the New Arcadian Press.

Drawing and family, family and drawing. This was the mantra Chris re-affirmed every year when he updated his biography for the latest edition of the New Arcadian Journal. Drawing and family, family and drawing. These were at the heart of Chris’s life.