Karyn Hinkle

Visual & Performing Arts Librarian, Lucille Caudill Little Fine Arts Library, University of Kentucky, U.S.A.

On Publishing Scholarly Journals as Artists’ Books: Yorkshire’s New Arcadian Journal (2020)

Introduction: A Personal Reception

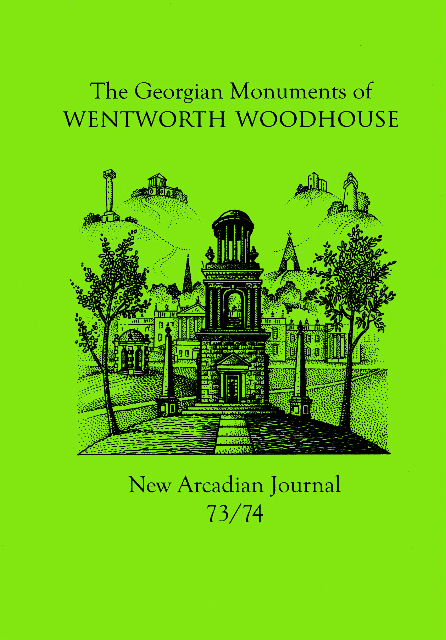

The first time I saw an issue of the New Arcadian Journal, it was 2008 and I was sitting at the reference desk of the Bard Graduate Center in New York City. I was flipping through a stack of newly-arrived periodicals issues, and among the slick pages of Apollo and the Journal of Design History, my hand stilled when it touched the strange beast that is The Georgian Landscapes of Wentworth Castle, or issue 63/64 of the New Arcadian Journal. The section-sewn volume has a soft, unlaminated cardstock cover in deep lilac colour, with the title and an incredibly detailed line drawing printed on the front in black ink. The simplicity of the design and the vivid paper make the book look both stark and jaunty at once. I opened the bright thing.

Fig. 1. Chris Broughton, cover and flyleaf drawings, NAJ 63/64 (2008)

This moment of initial contact marked the beginning of a long immersion in the world of the New Arcadian Journal (NAJ). After paging through 176 of issue 63/64’s thick, creamy pages, eyes popping at over 81 hand-drawn illustrations, I looked up the library’s holdings for the title. There was a rainbow-hued procession of dozens of section-sewn volumes in colours like dark teal, bright yellow, fuchsia. They each had scholarly titles about British estates and landscapes, and yet were all illustrated with artists’ drawings throughout. The earliest issues—much slimmer, staple-bound, with small lithographs pasted on the centre of the covers—revealed that the journal started life as a quarterly publication of poetry and other short texts like chapbooks, and my curiosity was permanently hooked. I was in the grip of what Johanna Drucker describes as the intense feeling one gets from certain artists’ books, which she calls auratic objects.[1] I felt the aura of the New Arcadian Journal immediately, in its individual issues as well as the entire run of the project as a whole. Drucker writes that “Books which have an aura about them generate a mystique, a sense of charged presence. They seem to bear meaning just in their being, their appearance, and their form through their iconography and materials […] qualities which produce a fascination which can’t be easily explained”.[2] She notes this feeling is different from interest or respect. Even though I feel both respect and interest for NAJ, the journal’s drawings, special covers, small press heritage, and esoteric subject matter impress their auratic power on a reader straight out of the mail and en masse on the shelf.

Fig. 2. The New Arcadian Journal, Bard Graduate Center Library (photo: Chantal Sulkow)

The New Arcadian Journal is not well-known among researchers in North America,[3] although it had been published in West Yorkshire from 1981to the present by the New Arcadian Press. The founder of the press, Patrick Eyres, describes NAJ as a “combination of artist-illustrations and scholarly texts”, which, Eyres writes for the press’ website, “investigates the cultural politics of historical landscapes by scrutinising their architecture, gardens, monuments, sculpture and inscriptions”.[4] Since the physical form of the publication is most closely related to fine press printing or artists’ books, and its content is most frequently related to the history of landscape, academic disciplines writing about landscape history and artists’ books are the communities most likely to publish work on the journal.

Fig. 3. Chris Broughton, the pressmark of the New Arcadian Press

Art historians who study the concrete poet and conceptual artist, Ian Hamilton Finlay, may also know NAJ because Eyres and the New Arcadian Press has a close relationship with Finlay, who collaborated on many issues of the journal.[5] However, perhaps because the press is located in Europe, the somewhat European-centred field of landscape history seems to have found the New Arcadian Journal more frequently than the more American-cantered field of the history of book arts has done so far. The title is also well known in garden history circles. This article promotes the book arts aspect of the project as an equally important contribution of the Journal.

Early History

The Journal’s first issue was published in 1981, and the latest to date is no. 75/76 on the Yorkshire landscapes of the 18th-century landscape designer Capability Brown (2016). There have been 53 issues of the journal published in total and they have evolved from slim art books into long, illustrated social histories of Georgian landscapes, art movements and politics.

Early issues from the 1980s were published quarterly, and included a lithographic print pasted to a brightly-coloured cardstock cover with just a few pages of a poem printed inside. A good example is issue 11, 1983. It is titled Arcady and it is described on the New Arcadian Press website as “the lyric manifesto of the New Arcadian Press”.[6]

Fig. 4. Howard Eaglestone, cover and title page drawings, NAJ 11 (1983)

The artist, Howard Eaglestone’s, cover illustration appears on a small, creamy-white coloured sheet affixed to a dark blue stock cover. At first glance a straightforward landscape scene with a lighthouse, the strong diagonal and vertical lines of Eaglestone’s drawing hold the viewer’s gaze until an uneasy sense of tension sets in. The central lighthouse rises into a dark, broody sky in the upper half of the image and rears over a crumbling—ancient?—amphitheatre whose blocky stones and stairs dominate the lower half of the picture. (But if it were an ancient amphitheatre, is a lighthouse exactly ancient? What is that doing there?). A more spare version of the scene from the same angle, also by Eaglestone, appears inside on the title page.

The credits on the last page of the Journal reveal that the illustrations depict Paphos, where the lighthouse was built in the late 19th century as part of a British military base.[7] It is located beside an ancient odeon amphitheatre, whose current limestone structure dates to Roman times and whose site as an odeon dates to the earliest settling of the island.[8] Howard Eaglestone’s cover drawing neatly juxtaposes antiquity with the martial; the angle of the composition allows the lighthouse to project like a missile from the ancient world below.

Such a juxtaposition embodies one of the New Arcadians and NAJ’s central themes: although popular conceptions of mythology might imagine Arcadia as a peaceful, lush place, a more accurate depiction of Arcadia would be a war-like, rocky place. As Patrick Eyres describes the NAJ’s stance, “Arcadia is far from a pastoral retreat but rather an emblem of the human predicament: ‘Woe to this land!’”[9] It is a theme the New Arcadian Journal reiterates throughout the early issues and returns to throughout the decades of publishing to come. The critic, Yves Abrioux, reports on this strand of their work by saying “The rigours of Sparta […] serve as a reminder of the true nature of Arcady […] the New Arcadians’ documentation of the theme brings out what is harshly militaristic in Arcadia”.[10]

For NAJ then, the garden is not always a safe and peaceful place, but often a more difficult site of controversy. The rest of the contents inside the Arcady issue continue to press that case. Eyres calls this issue “A metaphoric collage of Arcadian emblems, compiled as a lyric manifesto in poetry and prose”.[11] The issue contains 32 pages, most of which are spreads that feature a short text on the verso, such as a poem or excerpts from poems or other texts, and a small illustration on the recto by the artist, Ian Gardner. Fig. 5 shows two such spreads. ‘Ardent’, left, contrasts the flower, Love in the Mist, with terms like ‘Warships’. ‘ Apocalyptic’, right, carries on the morbidity with a skull-and-crossbones, but it also demonstrates NAJ’s humour, because it’s a rather cheerful one, almost like a child’s temporary tattoo.

Fig. 5. Ian Gardner, drawings, Patrick Eyres, texts, from Arcady: NAJ 11 (1983)

Another interior spread in the Arcady issue expresses two further aspects of the New Arcadian Journal’s work that will continue to appear in future issues. In Fig. 6, the twenty-eight detailed academic footnotes shown on the verso (which follow a preceding essay) represent the extensive scholarly research undertaken by the journal’s authors, especially in the later issues to come. On the recto, a visual arrangement of the word ‘arcadians’ functions like a work of concrete poetry that could symbolize the long association of the Journal with the concrete poet and artist Ian Hamilton Finlay, mentioned briefly above and further discussed below. These pages in an early issue bring together many strands of the NAJ, simultaneously demonstrating themes from its founding and the directions it heads later in terms of textual content, as well as illustration and physical form.

Fig. 6. Patrick Eyres, texts from Arcady, NAJ 11 (1983)

Later and Contemporary Issues

The later NAJ issues are published annually or biannually as book-length collections of essays by scholars, illustrated with prints and drawings by contemporary artists. A contributor to the journal, Jack Chesterman, affectionately describes them in the book arts journal Parenthesis, as “Electro-statically printed, comprising just over a hundred pages, A5 in format and on 120 gsm paper, these are chunky, purposeful volumes. While small enough to fit in a knapsack or poacher’s pocket for the explorer or journeyman, they have the weight and physical presence to ensure a sense of occasion for the fire hugging historian or armchair traveller”. [12]

Warlike Arcadia, or the garden as a site of controversy, continues as a theme, as do other recurring topics: Georgian landscape and architectural history; the work of Ian Hamilton Finlay; contemporary garden estates and garden estates in other eras outside the Georgian 18th century. The 2008 issue on Wentworth Castle discussed in the introduction is a good example of a very frequently recurring theme.

Fig. 7. Chris Broughton, cover drawings, NAJ 63/64 (2008), and right, NAJ 57/58 (2005)

Issue 63/64 turns out to be a new version of an earlier issue published three years earlier with the same title. Issue 57/58 contained essays by six writers, and sixty-nine illustrations by five artists, over its 172 pages. Their subject, Wentworth Castle, is described, characteristically chirpily, by Eyres on the New Arcadian Press website as “The innovatory Tory country estate whose symbolism is encoded with a treasonably Jacobite subtext”.[13] For the 2008 edition, described more sedately as being “revised and updated with new material and drawings including fresh insights into the Jacobite and Tory symbolism”,[14] the same six authors and five illustrators expand on their topic with twelve more illustrations and four more pages. They may have discovered new material while promoting the original publication; they may have also simply needed more Wentworth inventory, for the New Arcadians are experts on their long-running subject of the 18th-century Wentworth Castle and the related, nearby estate, Wentworth Woodhouse. The places are their close neighbours in Yorkshire, less than an hour from Leeds by car. Three other issues of NAJ and two other books published by the New Arcadian Press are about the Wentworths.[15]

Fig. 8. Chris Broughton, bird’s-eye views of Wentworth Woodhouse, left, and Wentworth Castle, double page spreads, NAJ 63/64 (2008)

Alongside the scholarly essays, full page spreads of immersive, technically accomplished ink pen drawings depicting the Wentworth Castle grounds by the artist, Chris Broughton, make clear the Journal is a work by artists. They join other elements by Broughton like the detailed view from the front gate that appears on the cover, and the repeat pattern illustration on the bright yellow endpapers, as well as smaller drawings reproduced throughout the issue by Catherine Aldred, Howard Eaglestone, Andrew Naylor and Mark Stewart—and more by Broughton—all of which enliven the text and reveal the journal’s aims as an art object.

Fig. 9. Catherine Aldred, Wentworth Castle, full page drawings, NAJ 63/64 (2008).

Critical Attention

Despite the New Arcadian Journal’s aesthetic intentions, the fields of garden and landscape history have given the journal more attention than the world of book arts has done. Dozens of reviews of NAJ can be found in publications with the word ‘Garden’, ‘Landscape’, or ‘Agriculture’ in their titles. A typical one for NAJ’s early issue on The Wentworths (issue 31/32, 1991), found in Britain’s Agricultural History Review, describes the volume as a “welcome and very enjoyable addition to the literature on garden design and landscaping in the eighteenth century” and mentions the authors’ “very close readings of the garden buildings and ornaments”.[16]

The New Arcadian Journal was included in the 2004-2005 exhibition at the British Library called The Writer in the Garden, and its curator, Roger Evans, wrote about the title in terms of its garden history contributions: “Over the years the NAJ has made a significant contribution to debates about garden history, and has also been the catalyst to the re-interpretation and even conservation of endangered landscapes”.[17] Toby Musgrave, author of a blog in the U.K. called Garden History Matters, is also typical of a landscape historian in his appreciation for the New Arcadian Journal: “The Journal” he writes, “is a wonderful publication—erudite, original and fascinating, and is a ‘must have’ for anyone interested in garden history and the relationships between gardens and the wider zeitgeist”.[18] And, reviewing NAJ in the Journal of Garden History, 18th-century cultural historian Stephen Bending writes that “Eyres’s strength lies, perhaps, in the breadth of his approach […] indeed this broad view of the landscape as industrial, social, and ‘aesthetic’ seems to be characteristic of the whole New Arcadian project”.[19]

As Bending indicates, the type of landscape writing the New Arcadian Journal publishes is important. Talking about the upper class, country-garden-club background from which a significant strand of garden history stems, Jack Chesterman explains that “the Journals are decidedly not ‘Heritage’ based or ‘National Trust’ inclined, although both these agencies may recognize the depth of knowledge and understanding contained within these publications”.[20] The latter certainly turned out to be true for NAJ’s latest (2016) Capability Brown issue, which was part of Britain’s official 300 year anniversary celebration of the landscape architect’s work funded by the Capability Brown Festival and Heritage Lottery Fund. The project saw an issue by the publisher of four decades of subversive garden history pictured in a photo collage with other books about Brown on the Research section of the official <www.capabilitybrown.org> website.[21] In a publicity image created for the festival, NAJ 75/76 is pictured second from the top of the stack, where its bright turquoise cover stands out (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Publicity for published research (image: the Capability Brown Festival 2016)

Sometimes the garden historians’ appreciation of the textual content in the New Arcadian Journal does cross into appreciation for its physical form and its nature as an art object. Writing in Garden History, David Lambert states “Garden History Society members will be familiar with the New Arcadian Press and its publications from the table of sumptuous wares originally displayed at the Society’s AGMs, manned by the genius of the enterprise, Dr Patrick Eyres. With the gorgeous coloured covers and unique combination of artist-illustrations and scholarly texts, the Journals are unique in garden publishing”.[22]

Fig. 11. The NAJs at the Small Publishers Fair, London

Although Lambert’s review focuses on the authors’ Georgian gardens research in NAJ 69/70 (2011), its impossible for him not to have noticed the remarkable (‘sumptuous’, ‘gorgeous’) physical form the Journal takes.

On the other hand, sometimes the aims of the garden historians reading the NAJ and the visual artists who publish it are at odds. When Charles Watkins, reviewing one of the Journals in the Agricultural History Review, says that “unfortunately the maps do not show the relationship between the two estates”,[23] he is complaining from the perspective of someone who would use the volume’s content for informational knowledge. The incredibly detailed and inventive work of the map makers (for example, Chris Broughton’s work pictured above at Fig. 8), who have known and drawn the estates over a long period of time, is lost on, unimportant, or even detrimental to the historian reading for informational content only. However, for the visual artist or the book arts researcher, who is reading the journal as a work of visual art, the illustrations are essential principles in and of themselves. As Tom Williamson writes when he reviews issue 53/54 of the New Arcadian Journal, “Particular praise must go to the artists whose line drawings—original, usually informative, sometimes evocative, occasionally just odd—help to give the volume its distinctive feel”.[24]

Fig. 12. Chris Broughton, cover and flyleaf drawings; Andrew Naylor, title page drawing, NAJ 53/54 (2002)

Like Williamson, Lambert understands the inextricable nature of the NAJ’s textual content and its physical shape as work-of-art. He writes that “As ever, the New Arcadian Journal presents its far-reaching revision of conventional wisdom in a combination of text and image. The images are slyly pointed: [Chris Broughton] merges a view of the Arcadian landscape of Cannon Hall in South Yorkshire with the slave-ship Cannon Hall”.[25] In this case again, the illustration is not a documentary depiction of the garden, and the artists and editors of the journal would never wish for it to be.

Fig. 13, Chris Broughton, the two Cannon Halls, double page spread, NAJ 69/70 (2011)

Though not as frequently as in garden history publications, the New Arcadian Journal has been discussed in book arts publications as well. Chesterman’s 2001 review appeared in Parenthesis, the British Fine Press Book Association’s journal, which “deals broadly in fine and private press printing as well as bookbinding, typography, collecting, publishing and related areas”.[26] NAJ was also included in a large artists’ books exhibition a few years later, which was organized by Impact Press in England and travelled to the United States: Arcadia Id Est: Artists’ Books, Nature and the Landscape: A Touring Exhibition of 111 Artists’ Books, 2005-2007.[27] Eyres writes in the exhibition catalogue that “Collaboration between artists and writers enables the annual New Arcadian Journal to excavate the archaeology of ‘place’ […] and so reveals the NAJ as a hybrid of artistic, poetic and scholarly responses to the site under scrutiny”.[28]

As Eyres notes, he and his contributors are scholars. NAJ issues are frequently cited in academic sources for the factual information they contain, such as books on Finlay’s work,[29] and art historical articles on the Journal’s other recurring themes like concrete poetry,[30] and 18th-century visual culture,[31] as well as garden and landscape histories.[32] Along these lines, another major scholarly contribution of the Journal is politics.

Fig. 14. Howard Eaglestone, cover and title page drawings; Chris Broughton, flyleaf design, NAJ 69/70 (2011)

An important, frequently referenced, and undoubtedly political issue of the New Arcadian Journal was published in 2011 entitled The Blackamoor & The Georgian Garden (NAJ 69/70). Along with its trademark hand-drawn illustrations and a striking pink cardstock for the cover, the issue includes five essays about British estate owners’ prevalent use of black bodies in garden statuary (Blackamoors) during the era when Britain and particularly the estate owners profited hugely from the Atlantic slave trade.[33] David Lambert writes, “It is a fascinating and shameful aspect of England’s heritage upon which this Journal sheds much needed light”.[34]

Fig. 15. Andrew Naylor, full page drawings, NAJ 69/70 (2011).

The Blackamoor issue takes a close look at the estates of Hampton Court Palace, Melbourne Hall and Wentworth Castle and the statues of black bodies that adorn them. Reviewing the issue in Garden History, Lambert writes, “Now the New Arcadians have fired a terrific salvo at the complacency and silence [about the role of slave wealth in garden history] … the Journal implicates gardens deeply in the profits of the slave trade and, more relevant to garden historians, reveals how slavery inspired significant elements in the decoration of eighteenth-century gardens”.[35]

Fig. 16. Andrew Naylor, full page drawings of the Wentworth Castle Blackamoor under restoration, NAJ 69/70 (2011)

Although the 2011 Blackamoor issue was the first time the New Arcadian Journal addressed the politics of the slave trade, the New Arcadians were no strangers to political controversy, having dedicated issues to the politics of the 18th-century Tories and Jacobites; to other politics of country houses; to issues on landscape conservation; and to the decades-long fight of Ian Hamilton Finlay with local tax authorities in the late 20th-century, termed The Little Spartan War. Stephen Bending, reviewing NAJ, calls the rhetoric “attractive in its forcefulness and overt political concern” and says “this emphasis on high politics throughout the essay is clearly fruitful and shows how iconographic readings of the garden can broaden our understanding of the cultural landscape”.[36]

Political and artistic, scholarly and handmade—thanks to its unique form and its enthusiastic following by artists in the U.K. as well as the outgoing personality of Patrick Eyres, the New Arcadian Journal has also received notice in the popular national press. Jennifer Potter reviewed it for TLS, London’s Times Literary Supplement, in 2008, writing “the starkly black-and-white illustrations in a variety of styles proclaim NAJ’s core qualities: eclectic, obsessive, bellicose (war planes flying low over Georgian statuary is a very New Arcadian image), and refreshingly original in its determination to offer a modern and highly particular reading of old landscapes”.[37]

Fig. 17. Chris Broughton, Hercules transporter over the Hercules Garden, Blair Castle, and right, Howard Eaglestone, F-111 over Rousham, full page drawings, NAJ 37/38 (1994)

A few years later, a feature in The Times, Register appeared in 2012, ‘A Green and Pleasant Three Decades’, by Stephen Anderton.[38] He writes, “It is no easy read, yet to those interested in gardens in the broadest sense it is fascinating”. He offers a useful interpretation of the artists’ illustrations: “The New Arcadian Journal uses a generous number of imaginative, characterful line drawings, rather than photographs. Look at Chris Broughton’s Privy Garden at Hampton Court Palace, or his imaginary slaving ship sailing through the parkland of its own Palladian mansion. It is a wonderful relief from the universal glitz of modern garden photography”.

Fig. 18. Chris Broughton, the Privy Garden, Hampton Court Palace, double page spread, NAJ 69/70 (2011)

So, while some reviewers, especially in the popular press, comment on the visual art aspects of the New Arcadian Journal, most writers have focused on its political content and its textual content in terms of garden and landscape history. To write more about how NAJ works as an aesthetic object and as an artists’ publication, it helps to take a closer look at the work of the artists involved with the project, of whom there are many.

The Journal as Artists’ Book

The founding members of the press—Patrick Eyres, Ian Gardner and Grahame Jones, joined by other poets and artists around Leeds—were close to the landscape and concrete artist Ian Hamilton Finlay. As Eyres mentions sometimes in his author and presenter bios and speaking engagements, he knew Finlay for nearly thirty years and has written at length about the artist, his work and his garden estate in Scotland, Little Sparta.[39] When Finlay died in 2006, Eyres wrote obituaries for him in Sculpture Journal and Garden History News, and Eyres served on the board of the Little Sparta Trust.[40]

Fig. 19. Howard Eaglestone, cover and title page drawings; Chris Broughton, flyleaf drawing, NAJ 39/40 (1995)

Ian Hamilton Finlay thus influenced, collaborated with, and figured frequently as a subject of the New Arcadian Journal. In the early 1960s, Finlay also ran a small printing press that published an art journal—his Wild Hawthorn Press published the artists’ periodical, Poor. Old. Tired. Horse [41]—in a nice symmetry of connection between Finlay’s work and Eyres’. Patrick Eyres writes at length about the New Arcadians’ connection to Finlay on the website,[42] and one of Finlay’s biographers, Yves Abrioux, writes in turn about Finlay’s connection to the New Arcadians, whom he calls Finlay’s “Yorkshire allies”, in Ian Hamilton Finlay: A Visual Primer: “In his exploration of [themes in his work], Finlay has been joined by a group of artists from Yorkshire, the New Arcadians, constituted in the early 1980s. (The group publishes the quarterly New Arcadians’ Journal”).[43] Writing in the early 1990s, Abrioux is describing a time at the beginning of the NAJ project, and he stresses their group nature: “a group of artists”, “the group publishes”. The New Arcadian Journal was a collaborative venture from the start.

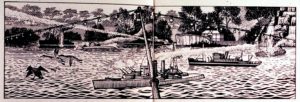

Fig. 20. Chris Broughton, ‘Naval Warfare’, Peasholm Park, Scarborough, double page spread, NAJ 39/40 (1996)

In time, Eyres’ two co-founders, Ian Gardner and Grahame Jones, left the New Arcadians and other artists joined in. The format of the journal shifted, as we’ve seen, from a slim quarterly publication to a book-length annual publication. A decade further into their history, Jack Chesterman wrote in his Parenthesis review that “Around [Eyres] a ’repertory company’ of writers and artists have changed and evolved over the years, evidencing a capacity to reinvent partnerships and collaborations”.[44] Through these changes, the collaborative ethos of the project remained a constant.

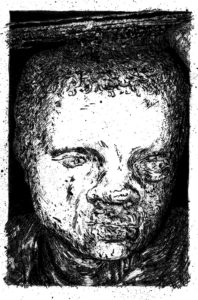

Because so many artists have been involved with the journal, research articles could be written on many different NAJ artists, some of whom teach at art schools in the area, others of whom are independent designers and illustrators, and who have worked briefly or for decades with the journal. This piece examines the work of three artists who are each readily associated with the New Arcadians. Between them, Howard Eaglestone, Catherine Aldred and Chris Broughton have contributed drawings to nearly every issue of the journal from the 1980s to the present day. Aldred’s work usually appears numerous times on interior pages throughout each of the contemporary era’s long issues; the same can be said of many issues for Eaglestone and Broughton, and drawings by Eaglestone and Broughton have appeared on the covers of 26 issues and counting.

Fig. 21. Catherine Aldred, parkland features at Hornby Castle and Burton Constable, NAJ 75/76 (2016)

Howard Eaglestone

As discussed above, Howard Eaglestone drew the broody cover illustration of NAJ 11, with the juxtaposed images of ancient amphitheatre with martial lighthouse (Fig. 4). That 1983 issue was among his earliest work with the New Arcadian group. In addition to the martial theme, the shape of the lighthouse conveys the bulbous top of the lighthouse, thus creating an undeniably phallic shape that perhaps forecasts a recurring motif in Eaglestone’s work for the Journal. Writing on the press’s website, Eaglestone says “An in-house joke is that my subject is frequently sex and/or the sea: a heady cocktail”.[45]

Fig. 22. Howard Eaglestone, cover drawing; Chris Broughton, flyleaf and and title page drawings, NAJ 49/50 (2000)

One of NAJ’s literally sexiest and most eye-catching issues is Gardens of Desire (NAJ 49/50), published in 2000; sample essays include ‘Upgrading Erections’ and ‘Sexuality and Politics in the Gardens’. This NAJ features an Eaglestone drawing on the cover (Figs. 22 and 23).

Fig. 23. Howard Eaglestone, cover drawing, NAJ 49/50 (2000)

The upward looking angle he choses for his illustration of a classical garden sculpture really lets the androgynous Bacchus rock her pose as he/she presides in fig leaf and diaphanous stole over a subtitle of sorts for this Journal: ‘Fay ce que Voudras’ (‘Do What You Will’) it reads, referring to the Rabelaisian quote and later Hell Fire Club motto that the Journal’s texts will wade into as they analyse the garden of the Hell Fire Club founder, Sir Francis Dashwood.[46] Heady, as Eaglestone says, indeed.

Catherine Aldred

The Gardens of Desire issue also has the distinction of publishing some of the illustrator and printmaker Catherine Aldred’s earliest work for the New Arcadian Journal. Her easily flowing ink pen drawings of Buckinghamshire’s West Wycombe Park bring a fresh buoyancy to the Journal’s visual look. They include one façade of West Wycombe House itself and three garden temples.

Fig. 24. Catherine Aldred, the mansion and three temples from Gardens of desire: NAJ 49/50 (2000)

The finely detailed but free and open-handed quality of her line drawings can be observed in her other work for other publications, such as spreads in weekend supplements for the newspapers, or in magazines like Yorkshire Life.

Fig. 25. Catherine Aldred, Cityscapes: Leeds (above) and York (images: <www.catherienaldred.co.uk>)

The Yorkshire cityscape is typical of Aldred’s work; she is well-known for her architectural drawings. When Jennifer Potter reviewed NAJ for TLS, she noted the “fluid, John Piper-esque line drawings of structures, foliage and occasional interiors by Catherine Aldred”.[47] Including an entire category for ‘foliage’ is very apt; in NAJ, Aldred’s architectural drawings are frequently paired with abundantly rendered leaves and plants. The top two images from Gardens of Desire shown above in Fig. 16 could have been drawn while Aldred sat under a tree: plants form the foreground of the drawings and frame the actual subjects of the illustrations in background. Similar compositions can be seen in her images of Wentworth, which she has drawn in both the summer and winter for the Journal.

Fig. 26. Catherine Aldred, Wentworth Castle, double page spread, NAJ 63/64 (2008)

In Fig. 26 (summertime), a leafy hedge in the left foreground takes up a full third of the drawing while in Fig. 27 (winter, right), the bare black branches of the tree at the top right were drawn with the thickest, blackest lines in the composition.

Fig. 27. Catherine Aldred, Wentworth Woodhouse: wintertime, right

In the last eighteen years, Aldred’s ink pen drawings have elevated the interior pages of nearly every issue of the New Arcadian Journal produced; her lively lines are able to depict the nature of the Journal’s landscapes, places and spaces just in the ways readers need in order to experience all that the NAJ expresses.

Chris Broughton

Finally, one of the artists most responsible for the New Arcadian Journal’s visual identity is Chris Broughton, who died in 2015 after working with the New Arcadians for over three decades. As the designer of the current and longest running pressmark for the New Arcadian Press (Fig. 3), his work is intertwined with the very identity of the group.[48] His twenty or so iconic cover illustrations for the journal and multitude of interior illustrations contribute much to NAJ’s signal mix of erudition, humour and fine art.

Fig. 28. Chris Broughton, cover, title page and interior drawings for NAJ 43/44, Stowe (1997)

Like Catherine Aldred’s drawings, Broughton’s convey a lot of detail, though in a different style. His clear and precise work for the Journal results in images as engrossing as the worlds of certain illustrated children’s books or the maps of lands on the endpapers of some history books or fantasy novels. He is known among NAJ readers for the bird’s-eye views of the landscapes and estates discussed in the Journal’s issues, although as we have seen in some critics complaints, they are not necessarily factual or documentary views of locations. Perhaps it would be more accurate to describe these images as bird’s-eye views of the themes each issue unearths and explores in the landscapes. However they are explained, viewers find Broughton’s illustrations beautiful to behold.

Fig. 29. Chris Broughton, bird’s-eye views of Painshill Park, left, and Wotton House, from the front covers of NAJ 67/68 (2010) and NAJ 65/66 (2009)

Chris Broughton’s bird’s-eye views are not drawn from maps or aerial photographs, and although they do show something of what one could see from above, they’re not exact likenesses. Instead, Broughton has selected elements from each place and arranged them in ways that fit the space of his illustration, giving viewers the important elements of each site and a way to grasp the site as a whole. Howard Eaglestone calls the bird’s-eye views ‘overviews’. He writes about Broughton’s work, saying “I thought every drawing by Chris was extraordinary, but particularly the overviews of the gardens. He seemed able to hover above the landscape and imagine the space beneath him. These overviews had the brilliant clarity of the London Tube Map combined with the magic of a garden occupied by Rupert Bear”.[49] The states of hovering over the landscape and imagining describe Broughton’s bird’s-eye views, and would also be a fitting description for the project of the New Arcadian Journal as a whole.

Fig. 30. Chris Broughton, bird’s-eye views of Wentworth Woodhouse and Stowe from NAJs 73/74 (2014), full page, and NAJ 49/50 (2000), double page spread

While writing about his long involvement with the New Arcadian Journal, Chris Broughton said, “One of the most enduring collaborations of my career has been with the New Arcadians—a band of artists and writers who produce a journal every year dedicated to research into the history, politics and poetics of landscape and gardens. I have worked with this group for over thirty years forming close friendships and sharing many good times and successes. The Journal has been a force for good in garden conservation and I am proud to have been part of it”.[50]

Fig. 31. Chris Broughton, an Ian Hamilton Finlay sculpture at Little Sparta, NAJ 75/76 (2016)

In the latest, 2016 issue of NAJ, the final illustrations by Chris Broughton, as well some earlier works, were published posthumously. Fig. 31 shows an Ian Hamilton Finlay sculpture in the garden at Little Sparta, as illustrated by Broughton for that issue. It is sad to think of future issues without the surprise of a new bird’s-eye view of the garden by Broughton. However, the artists, Eyres and their friends and readers have always prized and emphasised the collaborative process of writing, illustrating and putting together the Journal, and that practice will no doubt continue.

Jack Chesterman discussed the New Arcadians’ collaborative work process in his Parenthesis review. He discovered “the material for each edition and its theme is generated specifically for it by the writers and artists concerned. A part of the process involves the group meeting and often making journeys to research the subject. This notion of corporate endeavour is important to the New Arcadian Press, and in a way, what makes it so particular”.[51] Its fun to imagine the writers and artists bundling up in the winter or protecting themselves from midges in the summer as they set off on a group estate walking adventure in the north of England or Scotland or any other place their investigations into landscape take them.

Patrick Eyres has written about these outings as well: “Along with the drawings came the intimacy of friendship, the annual jaunts to walk the landscapes engaged by each NAJ, the genteel banter and reflective conversations—often in Headingley’s ‘Arcadia’ pub”.[52] That evident camaraderie and friendliness must surely extend itself to the many book arts, publishing, garden history, landscape conservation, and other academic and popular events Eyres attends and organizes on behalf of the New Arcadians. A charming March 2012 blog post by the author of a blog called <miladysboudoir.net> describes a chance encounter with one of many such events celebrating the New Arcadian Journal, which the author discovered via a flyer posted at the Leeds Library: Eyres, along with Howard Eaglestone and Catherine Aldred, gave a talk at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in conjunction with an exhibit of original drawings and other NAJ materials (‘Drawings and Proofs for the New Arcadian Journal: The Blackamoor’). <miladysboudoir.net> titled her post with a quotation from the evening, “Seriously Wacky and Occasionally Mad”, and describes the proceedings: “Enjoy a glass of wine, a powerpoint talk, see the display, talk with the illustrators, and look at the Institute’s Library”,[53] which is a well-suited example of NAJ’s outreach programme.

Fig. 32. NAJ 61/62 (2007). Left: Chris Broughton, cover drawing. Right: Gary Hincks, flyleaf and title page drawings

Though Chris Broughton is surely still very much missed, the Journal’s other long-time artists are as deeply involved in the press’s current and future projects as ever. Catherine Aldred wrote on her blog about another quintessential NAJ event at the Yorkshire Museum: “drinks reception, book launch and fantastic, entertaining lecture by Dr Patrick Eyres on the work of landscape gardener Humphry Repton”. This occasion launched the Press’s most recent publication. “Delighted”, she wrote, “that so many of my illustrations have been included in this sumptuous nearly 200 page full colour publication!” [54]

Conclusion: Another Personal Reception

One of the attractions of artists’ publications is their ability to transcend their local space and time to reach readers. They do so in the hands of individual readers, of course, and they also do it on a wider scale through libraries. As I related at the beginning of this essay, I first encountered the New Arcadian Journal in a library in America, and, in the course of writing about it, I mentioned the Journal to Chantal Sulkow, a current librarian at the Bard Graduate Center Library. She hadn’t encountered NAJ before, and when she went to the shelf to investigate, she reported feeling the same sense of wonder and attraction for the publication that I felt when I first met the title in the same library a decade earlier.[55] She began sending me pictures of what caught her eye—and did not want to stop looking: “More New Arcadian” she wrote, attaching a dozen new pictures, “and even more New Arcadian!” she wrote, attaching a dozen more.

Fig. 33. Chantal Sulkow, impressions of the New Arcadian Journal by a first time reader: cover, flyleaf and interior illustrations by Ian Gardner, John Tetley, Jo Chesterman and Grahame Jones.

Fig. 32 shows just a handful of the photographs Sulkow sent. Her immediate, unfiltered impression as a new reader manages to convey a range of particularly New Arcadian themes, such as their support by Yorkshire Arts; an older pressmark by Ian Gardner; the care they take with endpapers; the practice of including original prints and drawings by a wide variety of artists; the connection with Ian Hamilton Finlay and Little Sparta; the care Patrick Eyres takes to hand-number (and sometimes sign) each issue.

The New Arcadian Journal is a small-press, collaborative artists’ venture as well as a highly intellectual scholarly endeavour. It is a politically charged publication—advocating for artists’ rights, landscape conservation and attention to the past politics of country estates—and also a deliberately artistic project created through the work of many talented artists. Although its an unusual journal in any of the varied communities who value it, its presence enhances all of them.

Fig. 34. Andrew Naylor, cupids at Melbourne Hall, NAJ 69/70 (2011)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

[1] Johanna Drucker, ‘The Artists’ Book as a Rare and/or Auratic Object’, in The Century of Artists’ Books, 2nd ed. (New York: Granary Books, 2004): 93-120.

[2] Johanna Drucker, ‘The Artists’ Book as a Rare and/or Auratic Object’, in The Century of Artists’ Books, 2nd ed. (New York: Granary Books, 2004): 93-94.

[3] Karyn Hinkle, ’Collecting the New Arcadian Journal at Art Libraries in North America’ (poster, Art Libraries of North America, 2015).

[4] Patrick Eyres, ‘Welcome to the New Arcadian Press’, accessed June 1, 2018.

[5] Patrick Eyres, ‘Finlay in New Arcadian Works’, accessed June 1, 2018.

[6] Patrick Eyres, ‘Arcady’, accessed, June 1, 2018.

[7] See Wikipedia, ‘Paphos Lighthouse’, accessed June 1, 2018.

[8] See Wikipedia, ‘Paphos Ancient Odeon’, accessed June I, 2018.

[9] Patrick Eyres, ‘Arcady’, in A Cajun Chapbook: NAJ 33/34 (1992): 7.

[10] Yves Abrioux, ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’, in Ian Hamilton Finlay: A Visual Primer, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1992): 242.

[11] Patrick Eyres, ‘Arcady’, accessed, June 1, 2018.

[12] Jack Chesterman, ‘The New Arcadian Press’, Parenthesis 6 (2001): 25.

[13] Patrick Eyres, ‘The Georgian Landscapes of Wentworth Castle’ (NAJ 57/58, 2005), accessed June 1, 2018.

[14] Patrick Eyres, ‘The Georgian Landscapes of Wentworth Castle’ (NAJ 63/64, 2005), accessed June 1, 2018.

[15] See The Wentworths: NAJ 31.32 (1991); Wentworth Woodhouse: A Landscape of Georgian Monuments: NAJ 59/60 (2006); The Georgian Monuments of Wentworth Woodhouse: NAJ 73/74 (2014); Wentworth Castle and Georgian Political Gardening: Jacobites, Tories and Dissident Whigs, and Diplomats, Goldsmiths and Baroque Court Culture: Lord Raby in Berlin, The Hague and Wentworth Castle – both the proceedings of the 2010 and 2012 Wentworth Castle conferences and published on behalf of the Wentworth Castle Heritage Trust, 2012 and 2014.

[16] Charles Watkins, ‘Review of The Wentworths: Landscapes of Treason ad Virtue: The Gardens at Wentworth Castle and Wentworth Woodhouse in South Yorkshire by Patrick Eyres’, Agricultural History Review 40, no. 2 (1992): 198-199.

[17] Roger Evans, ed., The Writer in the Garden, exhibition catalogue (London: The British Library, 2004).

[18] Toby Musgrave, ‘The New Arcadian Journal’, Garden History Matters, December 21, 2012.

[19] Stephen bending, ‘New Arcadian Journal 31/32’ (review), Journal of Garden History, 13 (1993): 118.

[20] Jack Chesterman, ‘The New Arcadian Press’, Parenthesis 6 (2001): 24.

[21] Capability Brown Festival 2016, ‘Research’, accessed June 1, 2018.

[22] David Lambert, ‘Review of The Blackamoor & The Georgian Garden by Patrick Eyres’, Garden History, 40, no. 1 (2012): 161-162.

[23] Charles Watkins, ‘Review of The Wentworths: Landscapes of Treason ad Virtue: The Gardens at Wentworth Castle and Wentworth Woodhouse in South Yorkshire by Patrick Eyres’, Agricultural History Review 40, no. 2 (1992): 198-199.

[24] Tom Williamson, ‘Book Review: Patrick Eyres (ed.) Arcadian Greens Rural: William Shenstone and the Poetics of Landscape Gardening at The Leasowes, Hagley and Enville, and at Little Sparta (New Arcadian Journal, 53/54)’, Follies Journal: The Journal of The Folly Fellowship 3 (Winter 2003).

[25] David Lambert, ‘Review of The Blackamoor & The Georgian Garden by Patrick Eyres’, Garden History, 40, no. 1 (2012): 161-162.

[26] Fine Press Book Association, Parenthesis, accessed June 1, 2018.

[27] University of the West of England, ‘Arcadia Id Est: Touring Exhibition 2005-2007’, accessed June 1, 2018.

[28] Patrick Eyres, ‘On Site Specificity and Storytelling’, in Sarah Bodman (ed.), Arcadia Id Est: Artists’ Books, Nature and the Landscape: A Touring Exhibition of 111 Artists’ Books, 2005-2007, exhibition catalogue (Bristol: Impact Press, University of the West of England, 2006).

[29] See, for example, John Dixon Hunt, Nature Over Again: The Garden Art of Ian Hamilton Finlay (London: Reaktion Books, 2008).

[30] See, for example, Joy Sleeman, ‘Elegiac Inscription: A Discussion of Words in the Work of Ian Hamilton Finlay and Richard Long’, Sculpture Journal 18, no. 2 (2009): 189-203.

[31] See, for example, Maiken Umbach, ‘Classicism, Enlightenment and the ‘Other’: Thoughts on Decoding Eighteenth-Century Visual Culture’, Art History 25, no. 3 (2002): 319-341.

[32] See, for example, Marion Harney, Gardens & Landscapes in Historic Building Conservation (Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2014).

[33] Patrick Eyres, ‘The Blackamoor & The Georgian Garden’, accessed June 1, 2018.

[34] David Lambert, ‘Review of The Blackamoor & The Georgian Garden by Patrick Eyres’, Garden History, 40, no. 1 (2012): 162.

[35] David Lambert, ‘Review of The Blackamoor & The Georgian Garden by Patrick Eyres’, Garden History, 40, no. 1 (2012): 161.

[36] Stephen bending, ‘New Arcadian Journal 31/32’ (review), Journal of Garden History, 13 (1993): 118.

[37] Jennifer Potter, ‘New Arcadian Journal’, TLS: The Times Literary Supplement no. 5509 (October 31, 2008), 25-26.

[38] Stephen Anderton, ‘A Green and Pleasant Three Decades’, The Times, Register, June 30, 2012.

[39] See ‘Patrick Eyres’, University of Utrecht Centre for the Humanities, + Link, and ‘Garden Marathon 2011’, Serpentine Gallery, London, video, 21:44.

[40] Patrick Eyres, ‘Finlay & Little Sparta’, accessed June 1, 2018.

[41] Yves Abrioux, ‘Biographical Notes’, in Ian Hamilton Finlay: A Visual Primer, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1992): 1.

[42] Patrick Eyres, ‘Finlay in New Arcadian Works’, accessed June 1, 2018.

[43] Yves Abrioux, ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’, in Ian Hamilton Finlay: A Visual Primer, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1992): 241-242.

[44] Jack Chesterman, ‘The New Arcadian Press’, Parenthesis 6 (2001): 24.

[45] Howard Eaglestone, ‘Contact Us’, accessed June 1, 2018.

[46] See Richard Wheeler, ‘Pro Magna Charta or Fay ce que Voudras: Political and Moral Precedents for the Gardens of Sir Francis Dashwood at West Wycombe’, and Wendy Frith, ‘When Frankie Met Johnny: Sexuality and Politics in the Gardens at West Wycombe and Medmenham Abbey’, in Gardens of Desire: NAJ 49/50 (2000).

[47] Jennifer Potter, ‘New Arcadian Journal’, TLS: The Times Literary Supplement no. 5509 (October 31, 2008), 25-26.

[48] Patrick Eyres, ‘Pressmark’, accessed June 1, 2018.

[49] Howard Eaglestone, ‘Chris Broughton, In Memoriam’, accessed June 1, 2018.

[50] Chris Broughton, ‘New Arcadians’, last modified 2015.

[51] Jack Chesterman, ‘The New Arcadian Press’, Parenthesis 6 (2001): 24.

[52] Patrick Eyres, ‘Chris Broughton, In Memoriam’, accessed June I, 2018.

[53] <miladysboudoir.net> (blog), ‘Seriously Wacky and Occasionally Mad–the New Arcadian Journal’, March 8, 2012, + Link. The title is a quotation from Fiona Russell’s article on the New Arcadian Journal, ‘Jottings from the Journal’, Yorkshire Post Magazine (3 March 2012).

[54] Catherine Aldred, ‘On The Spot: The Yorkshire Red Books of Humphry Repton, landscape gardener’, May 9, 2018.

[55] Chantal Sulkow, email message to the author, June 19, 2018.